Kepler's Laws from Newton's Laws

Inference of the inverse-square law

Kepler’s third law (based on observation) gives a relation between the orbital period $T$ and the radius $R$ of the orbit:

$ T^2 \propto r^3 $

Consider the simple case of uniform circular motion with constant radius $r$ and constant speed $v$. Then $v = \frac{2\pi r}{T} \propto \frac{r}{T}$. Similarly, for the magnitude of the acceleration $a$ we have $a \propto \frac{v}{T}$.

Then assuming Kepler’s third law,

$ a \propto \dfrac{v}{T} \propto \dfrac{r}{T^2} \propto \dfrac{r}{r^3} \propto \dfrac{1}{r^2} $

Central forces

Newton gave a geometric argument to show that a central force does not change the area swept out by a planet.

If we consider $\vec{r}\times\vec{v}$, we see that $\vec{r}\times\vec{v}= \text{const}$ for a central force, because

$ \begin{aligned} \frac{d}{dt} \left(\vec{r} \times \vec{v}\right) &= \vec{r}\,' \times \vec{v} \;+\; \vec{r} \times \vec{v}\,' \cr &= \vec{v} \times \vec{v} \;+\; \vec{r} \times \vec{a} \cr &= 0 \end{aligned}$

The last equality holds because $\vec{v}\times\vec{v}=0$ for any vector $\vec{v}$ and $\vec{a}$ is in the direction $-\vec{r}$ for a central force.

If we let $\vec{b} = \vec{r}\times\vec{v}$, we have $\vec{b}\cdot\vec{r} = 0$ and $\vec{b}\cdot\vec{v} = 0$, so both the position and velocity vectors lie in the plane normal to $\vec{b}$.

This shows that, under the influence of a central force, the object’s trajectory is confined to a plane.

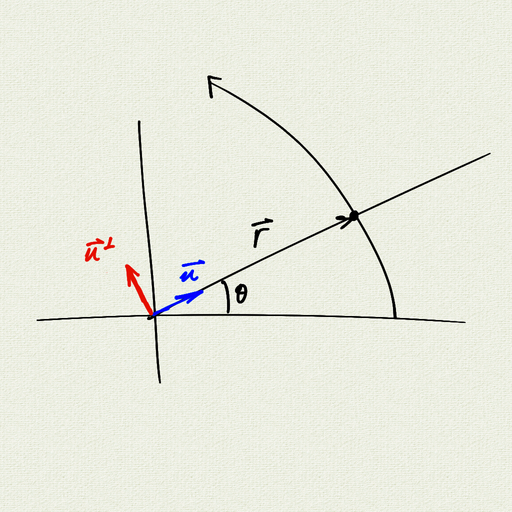

Polar Notation

Let $\vec{u}(t) = \begin{pmatrix} \cos\theta(t) \cr \sin\theta(t) \end{pmatrix}$, so we can write $\vec{r}(t) = r(t)\vec{u}(t)$. In other words, $r(t)$ is the distance from the origin, and $\vec{u}(t)$ is the unit vector in the direction of the position $\vec{r}(t)$.

Let $\vec{u}^{\perp} = \begin{pmatrix} -\sin\theta(t) \cr \cos\theta(t) \end{pmatrix}$ be the unit vector rotated $\frac{\pi}{2}$ from $\vec{u}$.

Note that $\dfrac{d}{dt}\vec{u} = \dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\vec{u}^{\perp}$ and $\dfrac{d}{dt}\vec{u}^{\perp} = -\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\vec{u}$. (Verify!)

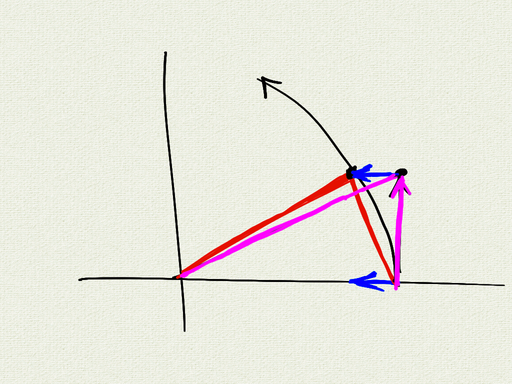

Equal area property

$\begin{aligned} \vec{r}\times\vec{v} &= \vec{r} \times \left( r'\vec{u} + r\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\vec{u}^{\perp} \right) \cr &= r'(\vec{r}\times\vec{u}) + r\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}(\vec{r}\times\vec{u}^{\perp}) \cr &= r^2 \dfrac{d\theta}{dt} \vec{k} \end{aligned}$

(Verify that $\vec{r}\times\vec{u} = 0$ and $\vec{r}\times\vec{u}^{\perp} = r\vec{k}$.)

The area swept out in a small time $dt$ is $dA \approx \frac{1}{2}r^2d\theta$, so the calculation above shows that $\dfrac{dA}{dt}$ is constant, equal areas are swept out in equal times.

Newton’s Laws

Newton’s Second Law:

$\vec{F} = m\vec{a}$

where $\vec{F}$ is the net force acting on an object, and $\vec{a} = \dfrac{d\vec{v}}{dt} = \dfrac{d^2\vec{r}}{dt}$ is the resulting acceleration.

Newton’s Universal Law of Gravition:

$\vec{F} = -\dfrac{GMm}{r^2} \vec{u}$

So the acceleration of an object due to gravity is:

$\vec{a} = -\dfrac{GM}{r^2}\vec{u}$

Relation between $\vec{v}$ and $\vec{u}$

Let $\vec{b} = \vec{r}\times\vec{v}$, which is constant. Then:

$\begin{aligned} \vec{a}\times\vec{b} &= \left(-\dfrac{GM}{r^2}\vec{u}\right) \times \left( r^2\dfrac{d\theta}{dt} \vec{k}\right) \cr &= -GM \dfrac{d\theta}{dt} (\vec{u}\times\vec{k}) \cr \end{aligned}$

(Notice the cancellation of $r^2$.)

We can simplify by noticing that:

$\begin{aligned} \dfrac{d\theta}{dt} (\vec{u}\times\vec{k}) &= \dfrac{d\theta}{dt} (-\vec{u}^{\perp}) \cr &= -\dfrac{d\vec{u}}{dt} \cr \end{aligned}$

This leaves us with a relation between $\vec{v}'$ and $\vec{u}'$:

$ \dfrac{d\vec{v}}{dt}\times\vec{b} = GM \dfrac{d\vec{u}}{dt} $

Integrating the above expression gives us a relation between $\vec{v}$ and $\vec{u}$:

$\vec{v}\times\vec{b} = GM\vec{u} + \vec{c}$,

where $\vec{c}$ is a constant.

Kepler’s Laws

$\vec{b} = \vec{r}\times\vec{v}$ is constant, so $|\vec{b}|$ is constant.

On the other hand,

$\begin{aligned} |\vec{b}|^2 &= (\vec{r}\times\vec{v}) \cdot \vec{b} \cr &= \vec{r} \cdot (\vec{v}\times\vec{b}) \cr &= \vec{r} \cdot (GM\vec{u} + \vec{c}) \cr &= GM\vec{r}\cdot\vec{u} + \vec{r}\cdot\vec{c} \cr &= GMr + rc\cos\theta \cr \end{aligned}$

Solving for $r$ as a function of $\theta$:

$\begin{aligned} r &= \dfrac{|b|^2}{GM + c\cos\theta} \cr \end{aligned}$

which is the polar form for a conic section. The curve will be an ellipse, parabola, or hyperbola, depending on the eccentricity $e = \frac{c}{GM}$.

One detail: The $\theta$ here is the angle between $\vec{r}$ and $\vec{c}$. We have assumed that $r$ is minimized at $\theta=0$, so $\vec{c}$ is actually in the direction of $\vec{i}$ and this is the same $\theta$ as above (the direction of $\vec{r}$).